Thinking the unthinkable: the collapse of the South Korea-U.S. alliance

Every U.S. official and every U.S. politician says the alliance is ironclad. Strangely, you often hear differently in Seoul.

Could the Korea - U.S. alliance end? It seems impossible. Every U.S. official and every U.S. politician says it’s impossible. Strangely, you hear differently here in Seoul. In fact, very differently.

Some say it’s all about Trump. If Trump is elected, the alliance will find itself on precarious ground. South Korea is low-hanging fruit - it’s an easier target than NATO and it’s a soft pick for economic leverage. Others say it has nothing to do with Trump. Even if Harris wins, there’s going to be difficult times ahead. Many in Washington confuse South Korea’s opposition to China’s dominance as pro-American. It’s not. It’s pro-Korean. Korea, they argue, is developing into a state that can steer its own future - the ultimate aim of both conservatives and progressives. Korea’s future in Korea’s hands. Is this how the Korea - U.S. alliance ends?

Let’s look at three factors that could occur (and ensure this is published before Tuesday): (1) a Trump Administration reluctance to uphold defense commitments; (2) the development of South Korean nuclear autonomy; and (3) the election of a popular nationalist South Korean leader.

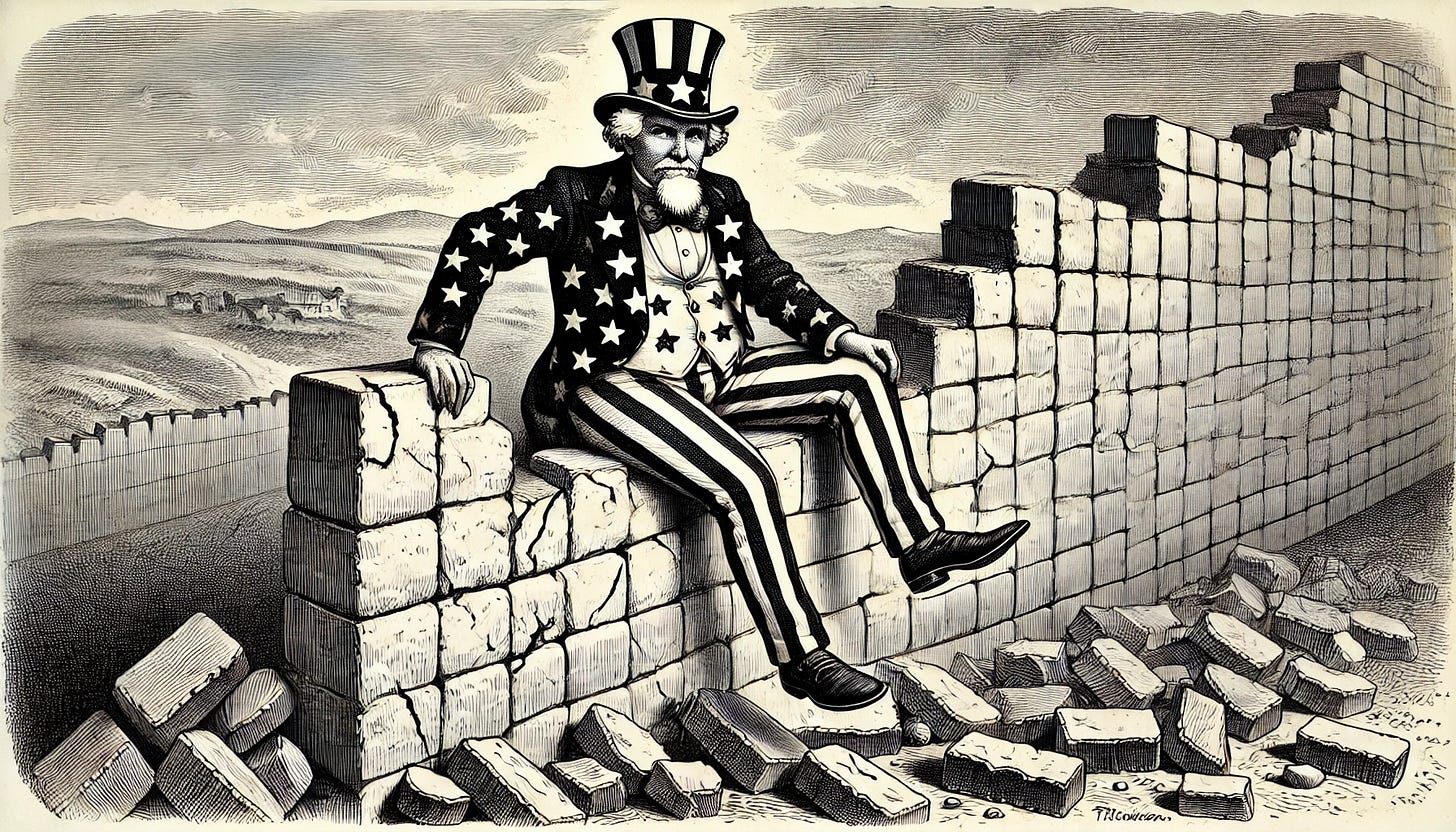

Reluctant America

One of Trump’s more consistent foreign policy beliefs has been that America’s allies should bear a greater share of their own defense costs. His approach views alliances through an economic lens, weighing military partnerships against their immediate financial costs to the U.S. In his previous administration, he pressured South Korea to increase its financial contributions to sustain U.S. troops on the peninsula, asking for as much as five times the amount Seoul had been paying. He’s already said he’ll do the same. South Korea, he claims, is a “cash machine”.

If Trump takes office again, there’s little reason to believe this stance would soften. Instead, we might see an even more drastic push for cost-sharing, where failure to meet financial demands could result in a rapid reduction or complete withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Korea. Despite the Yoon Administration’s close integration with the U.S. under Biden - indeed, perhaps because of it - South Korea will be a target. Such a move would send a powerful message that the U.S. is reconsidering its commitment to South Korean security, possibly encouraging Seoul to take more drastic measures for its defense.

Some argue that a reduced American presence could trigger a national reckoning in South Korea on whether to rely on the U.S. as a security partner. They fail to recognize that since the Korean War, South Korea has consistently and steadily pushed for ever greater autonomy within the constraints of the alliance. To date, it’s been near impossible to chart an independent course. Increasingly, this is less and less the case. South Korea today has an increasingly competent defense-industrial sector, indigenous technological development, and is even an important partner to America’s own defense-industrial sector. The next step? Reassessing its stance on nuclear development.

A nuclear South Korea?

In recent years, growing public support in South Korea for nuclear armament has emerged. Many in Washington see it as a reaction to North Korea’s advancing nuclear capabilities and the perceived limitations of the U.S. nuclear umbrella. This is not the complete picture. There is also political expediency, a distinct lack of a nuclear taboo, national pride, and the ever-present pursuit of autonomy and the capacity to act independently.

South Korean calls for nuclear independence could gain momentum under a Trump administration that appears reluctant to uphold defense guarantees. Indeed, it could even be aided by a Trump Administration that sees its own national security improved by having Chinese and North Korean nuclear weapons aimed at South Korea rather than Hawaii and California. A Trump Administration would more than likely go through several National Security Advisors - sooner or later, one of them will accept the conflated idea that a South Korea serves U.S. national interests.

Even if Harris is elected, the nuclear question could impact the alliance. A Harris Administration may respond to a South Korean nuclear breakout attempt with sanctions or other punitive measures, with the resulting discord forcing Seoul to question whether a reliance on the U.S. is tenable in the long term. A nuclear South Korea, once unthinkable, could fundamentally alter the balance of power in Northeast Asia and disrupt traditional security alignments, possibly encouraging Seoul to consider more independent or multilateral security arrangements.

A South Korean national populist

In the political landscape of South Korea, a leader’s stance on foreign policy and the U.S. alliance can have profound implications. Given the current political trends, the next South Korean president could be one with an inclination toward strategic autonomy or even non-alignment. This type of leader, more willing to distance South Korea from U.S. influence, could be propelled into office by a public increasingly wary of the U.S. alliance under a second Trump administration or a Harris Administration.

A South Korean president with a strong mandate for autonomy might advocate policies aimed at balancing relations between the U.S., China, and North Korea, rather than relying heavily on Washington. For instance, such a leader might seek deeper economic and diplomatic ties with China as a counterbalance, especially if relations with the U.S. are seen as overly transactional. This would represent a significant shift from traditional South Korean foreign policy, which has centered around a close partnership with the U.S. in order to deter North Korean aggression.

The unraveling

As these three factors converge, the potential for a gradual and perhaps inevitable dissolution of the ROK-U.S. alliance becomes real. Reduced U.S. military presence and defense commitments would heighten South Korean insecurity, pushing Seoul closer toward nuclear autonomy. A South Korean president who leans toward non-alignment could further catalyze this shift by pursuing policies that prioritize national autonomy over alliance loyalty. Over time, these cumulative tensions could erode the foundational trust of the alliance, weakening it to the point where it becomes a nominal rather than functional partnership.

In this scenario, the ramifications would extend far beyond the Korean Peninsula. Japan would likely reassess its own security policies, potentially pursuing its own military buildup or, in a drastic scenario, considering nuclear armament. China, meanwhile, would stand to benefit from a weakened U.S. influence in the region, using its economic and political power to draw South Korea closer into its orbit. The power vacuum created by a deteriorating ROK-U.S. alliance would introduce a new level of volatility in Northeast Asia, potentially sparking an arms race or even regional conflicts.

An important contrast may be Poland at the end of the Soviet Union. Poland did not immediately turn against the Soviet Union, it just turned away. That is all it takes for an empire to unravel.

The ROK-U.S. alliance has withstood decades of geopolitical storms. Regardless of who is elected, the pressures it will face in the next four to eight years could bring it to a breaking point. For South Korea, this could mean the end of its reliance on the U.S. security umbrella and the start of a more independent—yet risky—path forward. For the U.S., it could mean losing a crucial ally in the Indo-Pacific at a time of rising competition with China. The dissolution of the alliance may not be immediate, but as these speculative factors combine, the unthinkable might become a stark reality.