The humanities in the age of AI: renaissance rather than twilight?

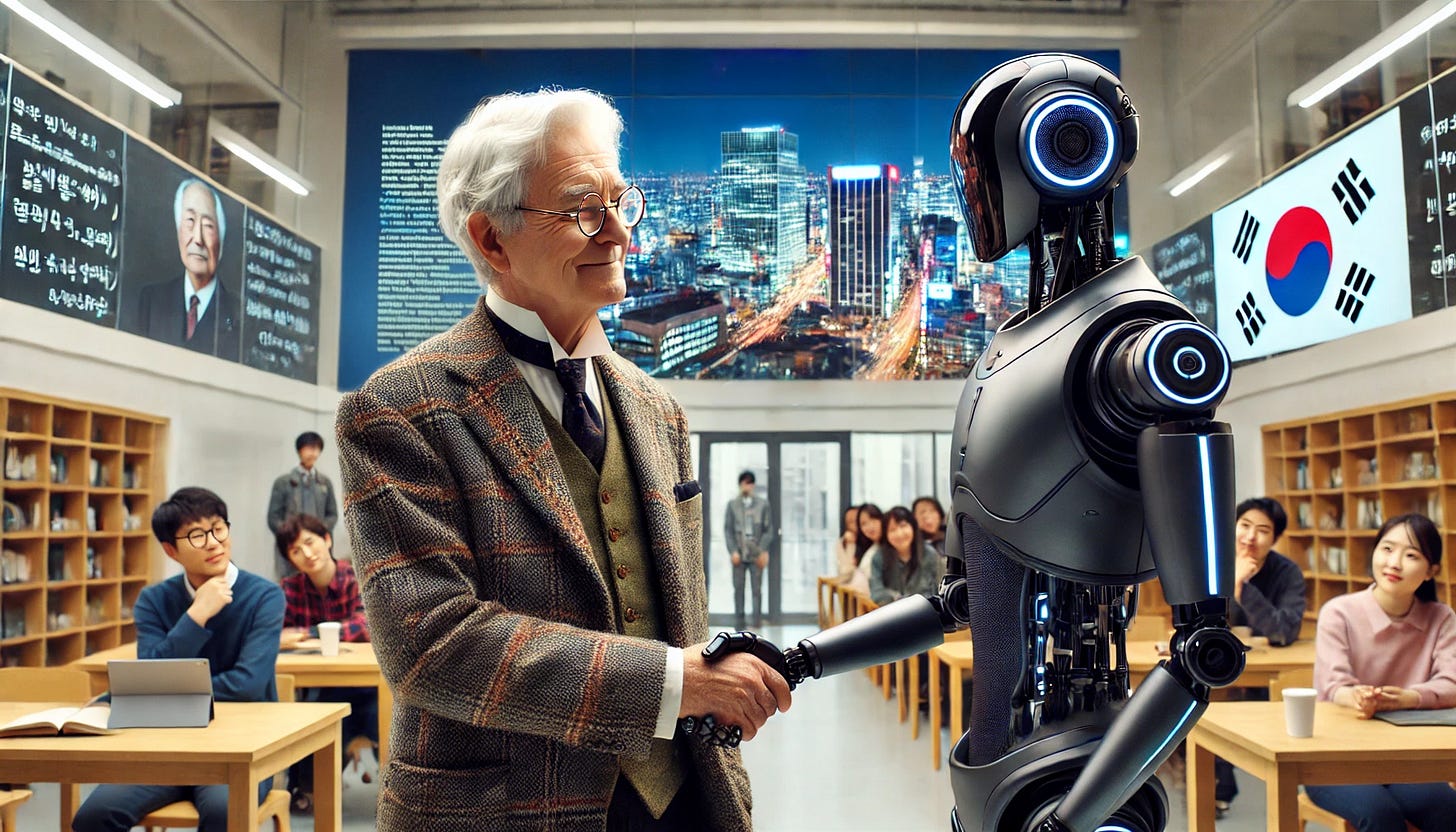

The rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI) increases the relevance of the humanities and those that realize this will get ahead.

For years, critics have lamented the decline of the humanities, particularly within the framework of the corporate university. The argument is well-rehearsed: as institutions prioritize STEM disciplines and vocational training, fields like philosophy, literature, history and creative writing appear increasingly irrelevant. In this narrative, the humanities are the casualty of economic pragmatism.

In particular, here in South Korea, as Gen-Z finds it harder and harder to secure employment, the response is to follow what went before - thin out the humanities and reinforce STEM and vocational courses. Increase class sizes and get them all prepping like to fit into the workforce.

What if this approach is fundamentally flawed? What if, instead of being on the verge of extinction, the humanities are about to experience a resurgence?

The rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has brought this question into sharp focus. AI can generate text, synthesize information, and mimic human expression, but it cannot replace the uniquely human faculties of broad understanding, ethical reasoning, empathy, and emotional depth—all of which are cultivated in the humanities. As corporate universities struggle to maintain relevance in an era where technical skills are increasingly automated, the value of a humanities-based education will become clearer than ever. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the field of international relations, where AI’s limitations underscore the indispensable role of human insight.

The international relations landscape is increasingly shaped by complex challenges: geopolitical conflicts, economic crises, climate change negotiations, and human rights issues. AI can process vast amounts of data and identify patterns, but it cannot replace the nuanced decision-making that diplomacy and global governance require. At its core, international relations is not just about processing information—it is about interpreting cultures, understanding history, and navigating the deeply human realm of power, trust, and negotiation.

For instance, AI may analyze diplomatic communications and predict potential flashpoints, but it lacks the ability to comprehend the historical grievances, cultural contexts, and emotional subtext that shape international conflicts. The resolution of tensions between nations requires not just data analysis but also the ability to read between the lines, anticipate unspoken concerns, and build relationships—skills deeply embedded in the humanities.

Diplomacy, at its heart, is about storytelling. Nations craft narratives to justify their actions, build alliances, and sway public opinion. Understanding these narratives—why they resonate, how they are constructed, and what historical wounds they reopen—requires expertise in literature, history, and cultural studies. AI can process speech patterns and track sentiment analysis, but it cannot replace the lived experience of understanding another person’s worldview.

Creative writing is an often overlooked skill in diplomatic training. Creative writing helps in diplomacy by fostering narrative skills, emotional intelligence, and cultural sensitivity—essential tools for effective communication and conflict resolution. Diplomats must craft compelling messages, frame narratives that resonate with diverse audiences, and navigate complex international relationships with nuance and persuasion. Storytelling, a core element of creative writing, enables diplomats to bridge cultural divides, humanize political issues, and build empathy, making negotiations and international relations more effective.

Take, for example, the ongoing tensions on the Korean Peninsula. While AI may analyze trade flows and military manoeuvres, it cannot grasp the depth of historical trauma that underpins North and South Korean relations. Effective diplomacy requires engaging with that history, recognizing the emotional weight of division, and crafting messages (and stories) that resonate with different audiences. These are humanities-driven skills, not technical ones.

An end to the corporate university?

The corporate university model—a system that prioritizes immediate marketability over intellectual depth—will soon come to an end. The promise of STEM fields has long been job security, but as AI automates coding, engineering, and even data science, the skills that remain indispensable will be those that machines cannot replicate: critical thinking, ethical reasoning, emotional intelligence, and cross-cultural understanding. The corporate university model, once predicated on aligning education with industry needs, will find itself ill-equipped to train students for a world where technical skills are increasingly automated.

Universities that recognize this shift will thrive. They will move beyond the corporate logic of productivity and efficiency and instead champion broad, interdisciplinary thinking. Degrees in philosophy, history, literature, or creative writing will no longer be dismissed as impractical; rather, they will be essential for shaping the human-AI relationship and guiding the ethical implications of emerging technologies.

Far from withering away, the humanities are poised for a renaissance. AI is not a threat to the humanities but rather a catalyst for their resurgence. The ability to think broadly, reason ethically, and understand human emotions will be the most valuable skills in an AI-driven world. In international relations—where history, diplomacy, and ethics converge—the need for humanists will be greater than ever.

South Korea is likely to be slow in embracing the humanities renaissance driven by AI, as its deeply ingrained corporate culture prioritizes efficiency, technical expertise, and rigid hierarchies over broad intellectual inquiry. The country’s intense focus on STEM education and its highly competitive job market reinforce a mindset where humanities disciplines are often seen as impractical.

With universities and businesses still emphasizing immediate economic utility, it may take longer for Korea to recognize that skills like critical thinking, narrative framing, and ethical reasoning—core to the humanities—are crucial in an AI-driven world. South Korea will fall behind. As global trends shift and the limitations of automation become clear, individuals in Korea will eventually have to adapt, albeit at a slower pace than some of their Western counterparts.