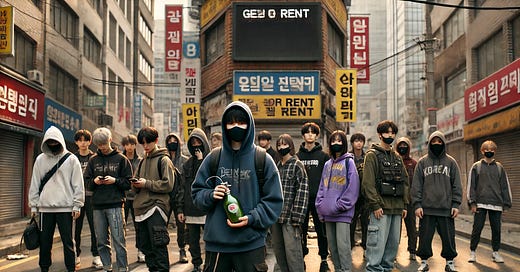

South Korea’s Gen-Z and the turn to extreme politics

When you take away the social contract, you cannot expect attitudes to the international to stay the same.

South Korea’s Gen-Z—those born from the mid-1990s to early 2010s—are coming of age in a country where the promises extended to previous generations no longer hold. For decades, South Korean society operated on a relatively predictable formula: study hard, enter a decent university, secure a job at a chaebol or in the public sector, buy a home, and prepare for a stable retirement.

That linear path is now broken. Young South Koreans can no longer secure what their parents took for granted - all that is left is the incessant competition and boundless consumption fed by social media. As the security net frays, and young South Koreans realize how they’ve been screwed, many are turning to political extremes. Young South Koreans are turning from the centrist status quo that failed them.

Employment? Think again. Once, a secure job at a major conglomerate (chaebol) like Hyundai, Samsung, or LG was the ultimate goal—and an achievable one. But today, that goalpost has moved. In a sign of the times, Hyundai this week announced a $21 billion investment plan—not in Korea, but in the United States, as a way to sidestep tariffs. “Great” says Joe average, Hong Gildong, “Hyundai will thrive, the stock owners will get richer, and I’ll have no job.” The auto-industry is a zero-sum game. Cars produced in the U.S. means less cars produced in South Korea. More jobs in the U.S. means less jobs in South Korea.

This reflects a broader trend: Korean conglomerates are increasingly directing capital and jobs overseas, chasing better market conditions, cheaper labor, and more stable geopolitical climates. For Korean youth, the message is clear—these companies are no longer investing in their future. Youth unemployment remains stubbornly high, and the few jobs available are often temporary, part-time, or contract-based, offering little in terms of career progression or security.

Affordable Housing? Think again. Not that anyone can afford a house without a job, but what about using that last path which enables a person to save - get a jeonse or key deposit? The country’s unique jeonse system, where tenants provide a lump-sum deposit instead of monthly rent, once allowed middle-class families to live in urban areas without drowning in debt. It was designed at a time when banks could not lend money, and agreements between landlord and tenants allowed private funds to be invested in small business and small manufacturing - vital contributions to a growing economy. But soaring property prices have made the jeonse system nearly inaccessible for young people. It’s today as much a means to hide money from authorities, scam the financially uneducated, or reap capital gains - all at the cost of Gen-Z. Korea’s housing crisis has become one of the defining economic issues of the younger generation.

South Korea now has one of the world’s highest levels of household debt, with much of it tied up in housing. Young people who manage to scrape together the resources for a jeonse deposit often rely on risky, high-interest loans. Others give up entirely, living with their parents well into their 30s, or moving to semi-basement apartments or distant suburbs with long commutes. Home ownership, once seen as a rite of passage into adulthood, is now a distant dream.

It’ll get better, right? Even long-term financial planning seems futile. South Korea’s National Pension Service (NPS), once considered a cornerstone of the social contract, is under severe strain. The government recently approved reforms aimed at shoring up the ₩1,100 trillion ($830 billion) fund. These reforms are widely seen as too little, too late. With Korea’s fertility rate at a record low and life expectancy climbing, the pension system will not be solvent by the time today’s Gen-Z reaches retirement. Gen-Z knows they’re paying tax and funding generations that are screwing them over, and leaving northing behind. How can they not be pissed off?

Faced with these realities, many young Koreans have little confidence they will ever retire comfortably. They’re told to invest early and diversify, but with no stable income or home, they have nothing to invest. The political consequences will soon come home to roost.

Time to change? This structural exclusion from key life milestones has started a growing political shift. South Korea’s Gen-Z is not turning to the left or right in the traditional sense. Some are escaping - seeking to leave the country or seeking alternative lifestyles in rural areas. Most are increasingly gravitating toward populist, reactionary, or radical reformist movements—depending on which side promises to tear down the system that has locked them out.

On the far right, there's growing sympathy for nationalist, anti-immigrant, and misogynist rhetoric, particularly among some young men who feel they are being unfairly disadvantaged in the name of gender equality. Online communities that promote anti-feminist sentiments have flourished, giving rise to political figures who champion “men’s rights” or critique “woke culture.”

On the other hand, parts of Gen-Z are swinging to the far left, embracing anti-capitalist, anti-chaebol, and pro-labor politics. These youth often support independent candidates who reject both the conservative People Power Party and the liberal Democratic Party, blaming both for upholding a broken status quo. Movements calling for universal basic income, massive public housing construction, or dismantling of corporate monopolies are gaining traction among these groups.

Unlike their millennial predecessors, who still held onto some version of the dream, Gen-Z in Korea is defined by disillusionment. The frustration is not simply economic—it’s existential. They’ve played by the rules, but the rewards are missing. College degrees don’t guarantee jobs. Jobs don’t guarantee homes. And homes don’t guarantee a future.

And foreign policy? Be prepared for some very significant change. Gen-Z has grown up with South Korea (and North Korea) facing off the globe and standing up. Whether it's South Korea captivating the world with its music and film, or North Korea outpacing and outmaneuvering the U.S to secure nukes, Gen-Z has seen the Korean Peninsula at the center. Their disillusionment is with how this success has been mismanaged by ruling classes in both Seoul and Pyongyang, which today look pretty similar in their ignorance, incapacity, and greed.

This means the norms of the U.S. alliance, unification (and separate development), historical attitudes towards Japan, and acceptance and willingness to engage with China, are all up for grabs. When you take away the social contract, you cannot expect attitudes to the international to stay the same.

In South Korea’s vacuum, extreme political views are flourishing. Whether in the form of street protests, online radicalization, or voting for outsider candidates, Gen-Z will increasingly demand a new social contract.

The question for Korea is not whether this generation will change politics—it is already starting to—but whether the political establishment can adapt before the discontent turns into permanent disengagement or something more explosive.