South Korea’s deeper democratic crisis lies in economic inequality

Disillusionment is setting in—not with a particular administration, but with the democratic process itself.

At first glance, South Korea’s democracy appears resilient. Martial law was imposed, swiftly overturned, and those responsible held to account. Protests were loud, legal, and effective. There was minimal violence, and supporters and opponents largely respected norms of behavior. Many read this sequence of events as a sign of democratic strength.

At second glance, South Korea’s democracy appears shakier. Human Rights Watch points to serious rights concerns regarding the misuse of defamation laws, increasing restrictions on protest, and the marginalization of vulnerable groups. These are overt threats—press freedom, surveillance, and protest restrictions. The steady weakening of democracy through the institutions created to support it - something seen across the democratic world.

At third glance, there is a more insidious danger, which runs just beneath the surface. Economic inequality is reshaping the foundations of South Korean democracy in a quieter, but more enduring way.

Inequality in South Korea is not new, but it is becoming more structurally embedded. The country has one of the highest relative poverty rates among OECD nations. Housing costs continue to soar, youth unemployment remains high, and older generations often retire into poverty. Despite high educational attainment, many young people face a narrowing path to economic security. And it does not seem like it will get better.

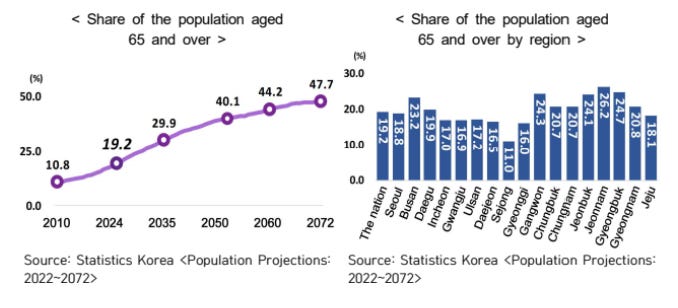

South Korea now holds the world’s lowest fertility rate, dropping to just 0.72 births per woman in 2024—a figure far below the replacement rate of 2.1. Demographic collapse is not a distant future scenario but a present-day reality, and its effects will define the lives of younger South Koreans.

As the population ages rapidly and the workforce shrinks, younger generations will face increased tax burdens to support pensions and healthcare for a growing elderly population.

They will also inherit an economy marked by slower growth and intensified competition for fewer opportunities. Social mobility is likely to stagnate further, while care responsibilities—once distributed across extended families—will concentrate on fewer individuals. In short, South Korea’s youth are being asked to sustain a system that is structurally unsustainable, without the security or incentives their parents once enjoyed.

Disillusionment is setting in—not with a particular administration, but with the democratic process itself.

This erosion of trust is not speculative. Polls show declining belief in the effectiveness of political participation, especially among younger Koreans. Voter turnout is falling. Cynicism about both major parties is growing. The perception that the system serves the interests of conglomerates and entrenched elites—rather than ordinary citizens—is no longer limited to fringe commentary. It is becoming mainstream sentiment.

Economic inequality is not just a social issue. It directly affects the stability of democratic norms. As more people feel excluded from economic progress, they disengage from the political system. They become less likely to vote, less likely to protest, and more susceptible to anti-system narratives. Democratic erosion, in this sense, doesn’t begin with a coup or emergency decree. It begins with economic exhaustion and political indifference.

The focus on rights abuses—while important—risks overlooking this deeper trend. Progressives and the conservatives will combat and flail their arms wildly over rights and rights abuses.

The beating heart of democracy in every state has always been a functioning and aspirational middle class. Laws can be repealed, institutions can be repaired, and leaders can be held accountable. But rebuilding the middle class and its inherent faith in democracy after years of economic stagnation and exclusion is far more difficult.

The next administration will inherit a political landscape shaped not only by recent constitutional crises, but by long-term structural inequality.

The danger is not that South Korea will experience another dramatic authoritarian rupture. The danger is that democracy will continue to function in form, while losing meaning in substance. The result is a system that appears intact but is increasingly disconnected from the lives of its citizens. And that, rather than any single crisis, is the more enduring threat.