Shamanism and Korean politics: Choosing the right time for a coup?

Rumors of shamanistic influence on the choice of day and hour to initiate a coup are swirling.

For those outside Korea, it’s hard to imagine that the country’s politics are influenced by centuries-old mysticism. Shamanism (musok), once a cornerstone of indigenous spirituality, has quietly evolved into a shadowy force in modern politics. While America has corporate funded think tanks and lobby groups (which are sometimes just as esoteric), Korea has shaman (mudang) whose supposed insights can influence everything from campaign strategies to crisis management.

For centuries, Korean shamans, often dismissed as relics of a pre-modern past, have played an outsized role in the lives of those desperate enough to seek their guidance. Historically, their rituals addressed agricultural woes and health crises, providing a blend of theater and hope to a largely rural society. Today, their clientele includes not just the desperate but the powerful—politicians keen to exploit spiritual beliefs to justify their actions or absolve their failures.

In a political climate marked by scandals and mistrust, it’s hardly surprising that some leaders resort to shamanic rituals. Why bother addressing real issues when you can hire a mudang to ward off “bad energy” or perform a kut (ritual) to guarantee electoral success? It’s governance by divine intervention, dressed up as tradition but often executed with more cynicism than Cambridge Analytica (the U.K. based firm that used Facebook data to disinform and sway public opinion in the lead up to Brexit).

Enter Choi Soon-sil

The infamous 2016 Choi Soon-sil scandal dragged shamanism from the periphery of Korean politics into the harsh glare of global scrutiny. As a confidante to then-President Park Geun-hye, Choi wielded astonishing influence over state affairs—her power allegedly derived from her connection to spirits. Whether these spirits had anything useful to say about economic policy or North Korean diplomacy remains unclear, but they certainly did wonders for fueling public outrage.

The public anger surrounding former president Park was fueled by revelations of her close ties to Choi, who allegedly exploited Park’s beliefs to wield power behind the scenes, reinforcing fears of corruption and nepotism. This scandal not only undermined public trust in the government but also highlighted lingering cultural tensions around shamanism’s role in modern Korea, ultimately leading to mass protests and Park’s impeachment.

Choi’s involvement in government was emblematic of a deeper issue: the normalization of superstition in high-level decision-making. Her influence over Park, reportedly bolstered by rituals and spiritual consultations, laid bare a system that allowed personal belief to override institutional accountability. The scandal revealed not just corruption but a bizarre mix of spiritual manipulation and political ineptitude that undermined public trust.

Beyond the spectacle of Choi Soon-sil, the darker side of shamanism in politics exposes its use as a weapon of fear and manipulation. Whisper campaigns about curses or spiritual retribution have long been employed to discredit rivals or galvanize support. This isn’t just folklore; it’s tactical slander, cloaked in the legitimacy of cultural tradition.

The rise of so-called "dark shamanism"—a term that encapsulates the alleged use of animal sacrifices, possession rituals, and other theatrics—represents the ultimate commodification of fear. Politicians seeking to intimidate opponents or distract the public from their own failures have found shamanism to be an effective, if ethically questionable, ally.

Shamanism and social media

In a hyperconnected world, even shamanism has gone digital. Mudang now leverage YouTube, live streaming, and social media to market their services, transforming a practice steeped in ancient tradition into a sleek, algorithm-friendly business (no endoresement or claims, but check out this one and this one for examples of social media shamans). Politicians, ever opportunistic, have not hesitated to tap into this trend. A well-placed video of a ritual or a shamanic endorsement can generate the kind of viral attention that conventional campaign ads can only dream of.

This digital shift hasn’t just expanded the audience for shamanism; it has also diluted its credibility. What was once an intimate, face-to-face interaction between practitioner and client is now a performance tailored for clicks and shares. Much like the Evangelist Christian money-hungry preachers in the U.S., shamans know their clientele and their weaknesses. The line between spiritual guidance and outright spectacle has never been thinner, and politicians are more than happy to exploit this ambiguity.

Korean society’s relationship with shamanism is a study in contradiction. On the one hand, it is dismissed as superstitious and backward, a vestige of a pre-modern Korea that many would rather forget. On the other, it persists as a cultural touchstone, invoked during moments of crisis or uncertainty. This paradox allows shamanism to thrive in the shadows, unregulated yet influential, ridiculed yet revered.

For politicians, this ambivalence is a gift. They can disavow shamanism publicly while engaging with it privately, weaponizing cultural heritage when it suits their agenda. The electorate, meanwhile, is left to question whether their leaders are guided by policy experts or by the whims of a spirit-possessed intermediary.

The right day for a coup?

Recent events have underscored this troubling dynamic. When President Yoon Suk-yeol declared martial law, ostensibly to eliminate "pro-North Korean anti-state forces" the rumors of shamanic involvement were not far behind. The unexpected and unprecedented political move culminated in the National Assembly voting to reverse the order, and the nation celebrated a landmark victory for democracy - but the question of why still confounds!

Amidst this chaos, rumors are swirling that Yoon's drastic action was influenced by shamanic counsel—a claim that, while unverified, gained traction due to his administration's alleged ties to shamanistic practices.

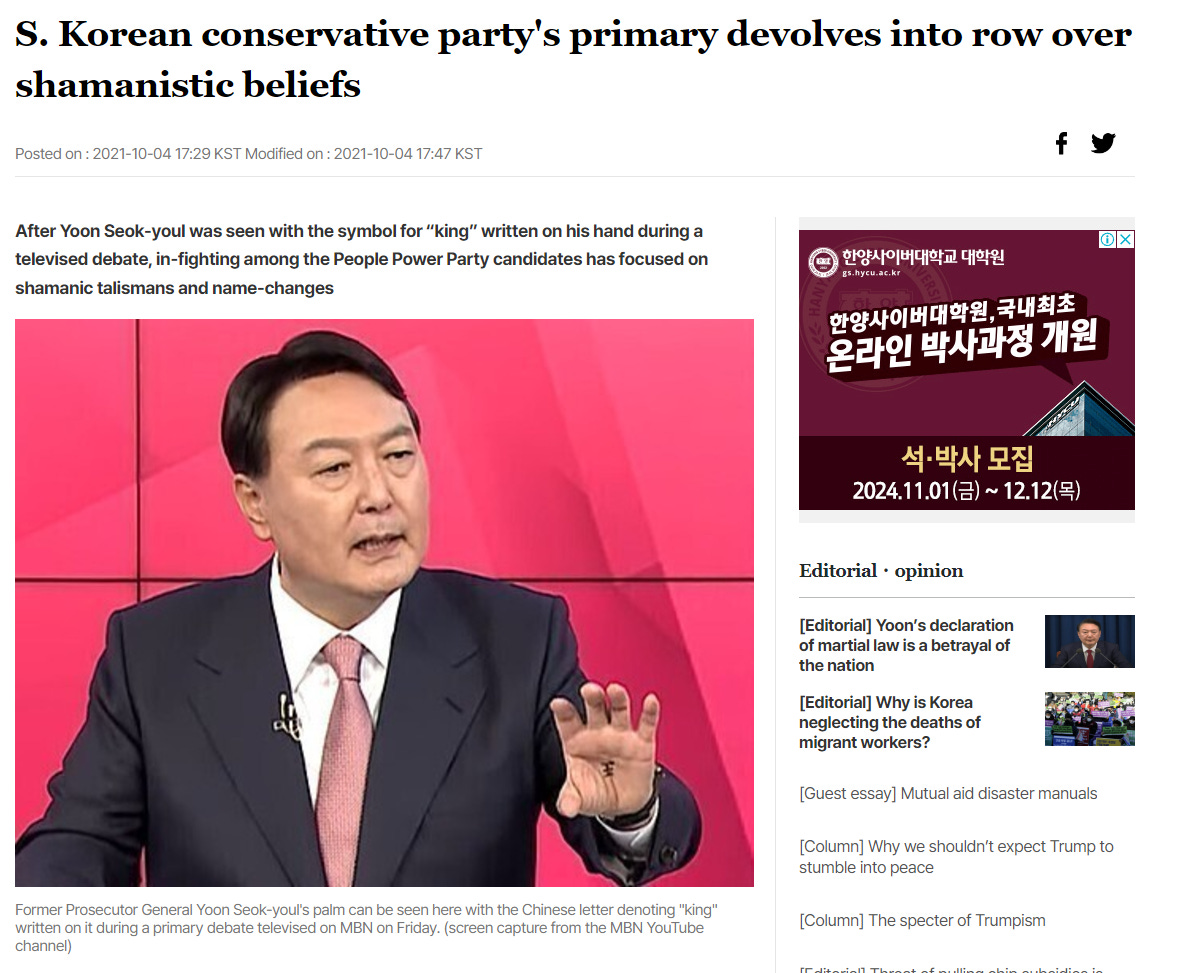

During the conservative party’s primaries, images spread widely of Yoon raising his hand to show the word “king” written in Chinese charaters. As reported in the the Hankyoreh Newspaper, his rival candidate Hong Joon-pyo noted in a Facebook post: “Seeing on the news about how [Yoon] is always consorting with shamanists, I had to wonder whether he’s trying to become a ‘shaman president.’”

In March 2022, Yoon announced plans to relocate the presidential office from the traditional Blue House to the Ministry of National Defense building in Yongsan. This move was intended to symbolize a departure from what he termed the "imperial" presidency and to foster closer communication with the public. The relocation was completed by May 10, 2022, coinciding with Yoon's inauguration, and the Blue House was subsequently opened to the public as a park. Despite official statements emphasizing transparency and accessibility, the decision faced criticism over its cost and potential security implications (others claim it was justified because the U.S. had bugged the Blue House so effectively, it could not be cleared without blowing up the building!).

Inevitably, unverified allegations surfaced, suggesting that shamanistic beliefs influenced the relocation, though these claims were firmly denied by Yoon's administration.

Such incidents highlight the peril of allowing superstition to seep into the corridors of power. When leaders prioritize esoteric rituals over empirical decision-making, the very foundations of democracy are at risk.

The enduring presence of shamanism in its political sphere serves as a reminder of the uneasy coexistence between tradition and modernity. While the nation projects an image of progress and innovation, its political system occasionally leans on practices that are anything but rational.

Perhaps the greatest irony is that shamanism, so often dismissed as anachronistic, remains deeply embedded in the mechanisms of power. It thrives not because it is valued but because it is useful—an unregulated, culturally ingrained tool that offers plausible deniability for those who wield it. In a democracy built on transparency and accountability, its persistence is both a symptom and a cause of deeper systemic flaws.

Image 1: “Mudang Performing a Ritual” at Wikipedia (Creative Commons Share-Alike 3.0 License)

Image 2: “Protest Of President Park Geun Hye” by Mathew Schwartz (Creative Commons Attribution 1.0)