Analysis: Marginal increase doesn't solve South Korea's demographic crisis

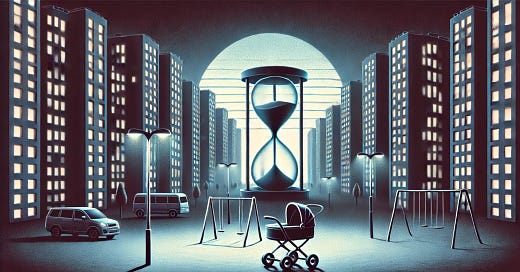

South Korea's population is on track to halve by the end of the century, undermining economic growth, labor markets, and social stability.

Significance: South Korea’s demographic crisis is the defining challenge of its economic, social and potentially security landscape. Government policies focused on work-family balance, childcare, and housing do not address the full scope of the problem. The nation’s population is on track to halve by the end of the century, undermining economic growth, labor markets, and social stability.

The demographic crisis is driven by entrenched structural issues, including labor market rigidity, an unsustainable education system, and a stagnant immigration framework. Despite a marginal increase in 2024, the fertility rate remains amongst the lowest globally. The long-term consequences will reshape South Korea’s domestic stability and international economic standing.

Analysis: South Korea’s fertility rate has been in continuous decline for decades, falling below the replacement level in 1983. Economic development policies of the late 20th century focused on population control but failed to anticipate long-term consequences. A highly rigid education system, hyper-competitive job market, and extreme work culture have led many young Koreans to reject marriage and parenthood.

The rising cost of living, stagnant wages, and career instability further deter family formation. Over $200 billion has been spent on pro-natal policies over the past 16 years, yet birth rates continued to decline until 2024, demonstrating that financial incentives alone are insufficient.

The marginal increase in births in 2024 was primarily due to postponed pandemic-era marriages, and the trend does not yet indicate sustained recovery. The rigid corporate hierarchy, long working hours, and a gender-imbalanced labor market discourage childbirth. The job market remains divided between secure positions in chaebols (large conglomerates) and precarious roles in smaller firms, making financial security difficult to achieve for young couples.

The government’s goal of raising the fertility rate to 1.0 by 2030 is unrealistic without addressing these fundamental labor and social issues. The continued reluctance to reform immigration policies exacerbates the issue, limiting options for workforce sustainability.

The absence of a proactive immigration strategy places South Korea at a disadvantage compared to nations that can successfully attract global talent, yet at the same time enables the maintenance of social cohesion.

Immigration remains an unsuitable policy solution for South Korean policymakers due to both domestic opposition and global trends. South Korea has a strong cultural preference for ethnic homogeneity, and there is widespread public resistance to large-scale immigration. Efforts to introduce foreign laborers have often met backlash, with concerns over social integration and job competition. In particular, resisting immigration has been highlighted as a key concern of the Gen-Z political movement - a key swing vote in domestic politics.

Furthermore, immigration has become increasingly unpopular worldwide, with many developed nations tightening their migration policies due to economic concerns, national security issues, social and political pressures. For South Korea, these concerns present a cautionary sign that large scale immigration may not be a solution. Even if South Korea were to open its doors to immigrants, attracting skilled foreign workers remains difficult, as the country ranks low in global talent competitiveness. Without a fundamental shift in public perception and policy, immigration will remain a politically and socially challenging approach to addressing the demographic crisis.

Mainstream media reporting focuses predominantly on government efforts to improve work-family balance, childcare, and housing but neglects key structural issues. The coverage does not adequately address the declining global competitiveness of South Korea’s labor force, the impact of excessive work hours on family planning, or the growing brain drain. The persistent focus on short-term policy fixes obscures the fundamental socio-economic transformations required to stabilize demographic trends.

South Korea’s demographic crisis presents a structural threat to its national security by eroding the foundations of its military, economic, and societal resilience. The country faces a shrinking conscription pool, forcing either reductions in force size, reliance on technological offsets, or shifts toward a more professionalized military—each with strategic trade-offs. The economic burden of an aging population already constrains defense budgets, potentially limiting long-term investment in advanced military capabilities. Demographic decline weakens societal cohesion, reducing the state’s capacity to sustain prolonged security commitments.

In a region defined by great-power competition and an unresolved conflict with North Korea, these pressures compound South Korea’s strategic vulnerabilities, necessitating policy adaptations to mitigate the national security risks of demographic decline.

South Korea’s demographic crisis also weakens its economic and geopolitical standing. A shrinking workforce and aging population will reduce productivity, eroding South Korea’s position as a regional economic leader. The country’s reliance on technological and industrial sectors will become increasingly unsustainable without an expanded labor force. Diplomatic engagements with Southeast Asia and other regions will need to intensify as South Korea seeks labor and economic partnerships to mitigate its population decline.

Impact: In the short term (0-12 months) the ongoing domestic political uncertainty will prevent sustained attention on demographics. In the medium term (1-2 years), labor shortages will continue to impact economic growth, increasing pressure for reform. In the long term (2-5 years), South Korea will face intensified workforce shortages, forcing either a significant policy shift toward skilled immigration or deeper economic stagnation.

I respectfully disagree. From a global perspective, South Korea is leading a trend toward declining population that will perhaps save the planet in the next hundred years. There is no evidence that technological developments can even slow, let alone reverse, the accelerating destruction of the global environment. We are currently above 8 billion humans on the Earth, when its sustainable carrying capacity has been estimated to be about half that number. National GDP is not the number we should focus on. Per-capita GDP is the place to focus. A good economic system should be able to adjust to a transitionally aging population and falling total national product. Severe climate change and large-scale species die-off cannot so easily be recovered from.