Is South Korea really a middle power?

South Korea lacks sustainable and intellectually creative middle power policy initiatives

Google Scholar academic citations during 2008–18 for the terms ‘South Korea’ and ‘middle power’ return 4260 hits — nearly double that of ‘middle power’ and Mexico (2060), Turkey (1990) and Indonesia (2850) and only just behind Canada (4420) and Australia (4380). South Korea has succeeded in promoting itself as a middle power.

South Korea fits the bill under any number of the myriad contested middle power definitions. But despite the flood of academic papers, think tank reports, workshops and seminars on the topic, there appears to be few ideas on how being a middle power helps resolve Korean Peninsula issues.

Middle powers such as Australia, Canada, the Netherlands and Sweden are characterised by satisfaction with the ‘status quo’ international order. Having reached an enviable position in the international hierarchy, their interest lies in strengthening the status quo by facilitating rules-based governance systems that constrain the states above them and sustain dominance over states below them. The very nature of being a divided state with the potential to drastically change the status quo could preclude South Korea from the middle power category.

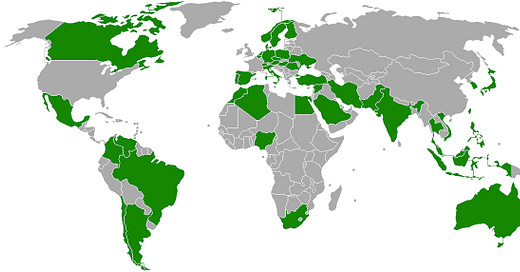

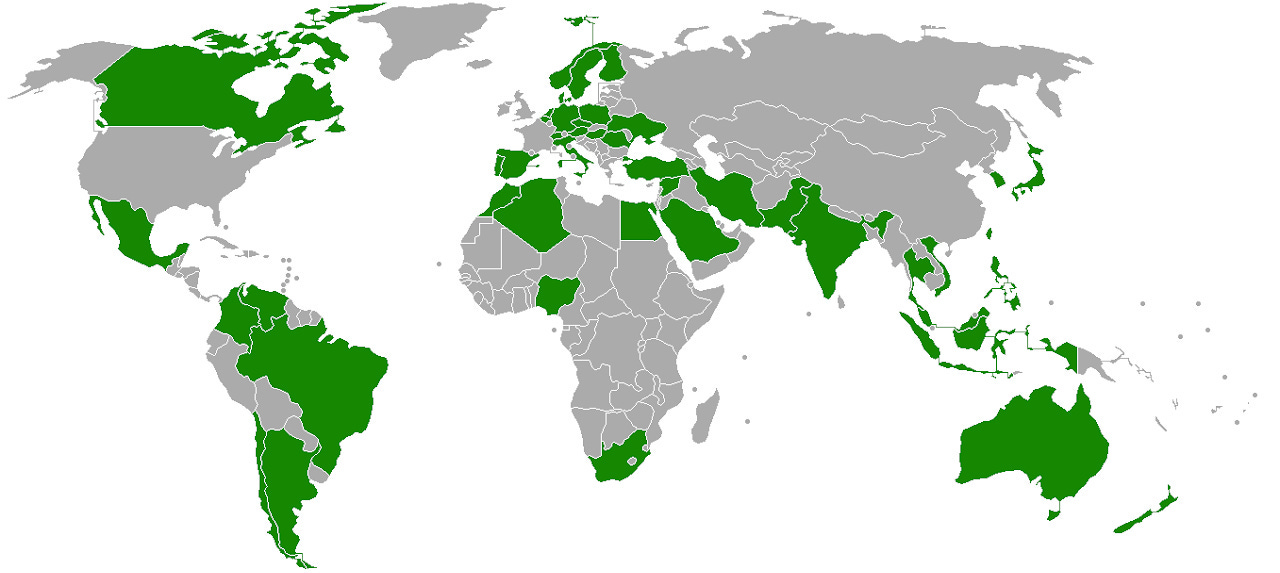

Middle powers are also routinely characterised by diplomatic behaviour. They use energetic and creative diplomacy, focus resources in niche areas to secure optimal results, strengthen influence through coalition building and portray what is ultimately self-interest as globally significant ‘good international citizenship’. To date, South Korea’s diplomacy has included engaging smaller states at the Winter Olympics ‘peace games’, ASEAN and MIKTA through regular dialogue mechanisms, and other bilateral partners through routine visits. However, there is no creativity, niche diplomacy, coalition building or good international citizenship to be seen.

During periods of heightened security tension, middle powers are supposed to follow the hegemon until directly threatened, while during periods of lower security tension, middle powers distance themselves and seek to constrain the hegemon’s actions. When coupled with the uncertainties of international politics, the on-again, off-again nature of security tension on the Korean Peninsula means that windows of opportunity for middle power initiatives are few and far between.

Successful middle power initiatives require not only timing but also sustainability, which is assured through continuity and consistency. With single five-year presidential terms, bureaucratic inertia at the beginning and end of presidential terms and a weak party system, South Korea’s foreign policy lacks continuity. Sources of ideas, influence and decision-making change between administrations. This is occurring with the current administration as influence moves from traditional foreign policy circles to national intelligence circles. For this reason, South Korea failed to sustain momentum on previous highly successful niche initiatives, such as green growth, aid effectiveness and nuclear security and infrastructure exports. The current constitution and party system constrains South Korea’s capacity to act as a middle power.

Successful middle power policy initiatives, such as the Cairns Group, APEC, the Cambodia Peace Settlement or the Ottawa Treaty, are what really make middle powers. Labelling several leftover, disparate countries in the G20 as a grouping, as was done with MIKTA, is not enough. Middle power policy initiatives have clear purposes, are well structured and planned and, above all, are intellectually creative. What then could a middle power policy initiative on the Korean Peninsula look like?

South Korea needs to increase its leverage vis-a-vis major powers. The first step should be a non-threatening intellectual instrument to increase influence, such as an international commission. An international commission may hold persuasive moral power if it is led by highly-respected and experienced senior political figures and is backed by the institutional capacity of South Korea and another middle power, such as the Netherlands. In much the same way as the report of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty transformed global thinking on the responsibility of states, a report on a peace regime for the Korean Peninsula could transform and influence thinking. This would give South Korea greater influence in interacting with major powers.

South Korea also needs to secure active support for its policies. Decades of visiting politicians’ publicity shots at the DMZ and intermittent North Korean provocations have failed to transform global concern into global action. South Korea needs active middle power participation to build peace — before they are asked to support conflict. The establishment of a ‘secondary-level council of states’ that consists of middle powers to help plan, coordinate and facilitate an evolving peace regime would bolster support for South Korean policy. With the participation of ASEAN and the European Union, such a council could add substantial weight to the South Korean voice amid the unbridled self-interest of major powers.

It may be too early to judge the Moon administration’s diplomatic efforts. But if we take lessons from history, the current window of opportunity to build middle power initiatives will close again soon. Being a middle power ‘in between’ two major powers or being a middle power by merely promoting the country as such was never enough and never will be. South Korea may be a middle power but sustainable and intellectually creative middle power policy initiatives are yet to emerge.

As published 2 May 2018 East Asia Forum.